Hide and seek: seeing beyond sight

Yom Kippur message by Rabbi Will Berkovitz

September 21, 2007

Several months back The Washington Post conducted an experiment. They wanted to know what would happen if Joshua Bell, one of the world’s finest violinists, playing one of the best violins ever crafted was to perform 10 of the most elegant pieces of music ever written. But dressed as an ordinary street musician in one of the most mundane places – a subway station in Washington, D.C. during the morning commute. The question they wanted to explore was, in a banal setting, at an inconvenient time, would beauty – would genius transcend? Is there something deeply rooted in the human soul that can rise above the white noise – the blindness that comes with familiarity.

Would a crowd gather? Would people willingly miss there trains, turn off their cell phones, take off their Ipods. Would people slow down, be late for work and find themselves inexplicably drawn in to the music? The answer was no.

That Friday morning passed like so many others. A crowd did not gather. They did not miss their trains and did not show up late for work. In fact 1,070 people passed by and virtually no one noticed –a scant 7 people paused. For his 45 minute performance this world renowned violinist made $32 and change. Few people even bothered too look. Something in our goal driven society, in our destination oriented culture created an astounding lack of vision. Blindness isn’t just an inability to see, but also the inability to edit – to appreciate what we are seeing – or to distinguish anything at all. In our frantic rush forward our lives are becoming diminished.

My photographer friend Tony lead me to the Washington Post story because it related to a book project that was consuming him. He had been reflecting on the nature of sight and shadows after spending five years teaching blind students the art of photography.

While looking over the photos my friend found himself compelled not only by what his blind students had created but what it had to say about our own lack of vision. He asked one student, “How do you not cut people’s head’s in your photos?” The student replied, “Just ask people where they are? These blind students had learned what we need to learn, how to see deeply by listening closely to our world.

The Talmudic word for blindness is sagi nahor. The literal translation is not blindness, but great light. It is as if the rabbis are saying that people become blinded by seeing too much. Or too much of the same thing. The people in the Washington subway couldn’t see or hear the violinist because they have walked those steps so many times that they lost the ability to encounter anything unexpected.

We see roughly 30 % of the sun’s light. Even with 20/20 vision we walk around oblivious to what is perfectly visible to many animals. So much is obscured by a fog drifting before us as we edit and splice of our way through our lives.

Most of us have a vague fear of losing our various senses. But while we may be able to buy glasses with stylish frames to correct our sight or a hearing aid the size of a pea to amplify the ambient sound the sense we are truly losing is something far more profound – Our ability to hear beyond listening – our ability to “see beyond sight.”

There was a constant group of people who tried to stop and listen to the music in that subway station – People who fought against the demands and the time lines of others. People who tried to push back on the strain of society and were drawn toward the music and the voice of the lone violin. People who heard beauty that day. Who recognized genius. And in each case, despite their greatest efforts, they were whisked away to the subways or the doors leading to the streets – to other’s destinations.

It was always the children. Whenever a child crossed those few steps between here and there. Whenever a young boy or girl entered that in-between space and was enveloped by the music, caught site of the violinist casting out notes like hooks, beauty did transcend. They recognized what the people around them could neither see nor hear.

But what distortion happens between here and there. What is the distance between young and old that is measured by something far greater than years? What get’s lost and when, and how and why. Where does it happen? Who pulls us away? When our truest longing is to stay and linger? And be drawn in? For a moment or a lifetime? Is there a way to keep our souls from becoming calcified – to remove the cataracts? Remove the beliefs that we have built up and fortified with our reason, our emotion, or our pain. Can we regain our vision – our ability to distinguish?

We see what we expect to see. We hear what we want to hear. And we experience what we anticipate we will experience. And we do it with all the instinctiveness of breathing. We do not expect to see a world class musician on the side of the road so we don’t see him even if he is there. We don’t expect our roommates or our spouses to wash the dishes so we don’t notice when the sink is empty. We are so use to being criticized that we can not hear a true compliment. We only see the same old parent tyrannically hurling the same old silences and aggression so we are blind to the sadness, loneliness or fear that have crept in over the years. We can’t begin to forgive because we have put our emotions on mute.

What we see has little to do with what is before us, and has everything to do with our experience and how we piece together our narrative. Our lives would be transformed if we could let go of what we expect to find before we begin the search. If we could wait for the question before settling on the answer. If we could attempt to understand before being understood. Like Hagar when she was cast out by Abraham, if we could lift up our eyes, we might begin to see a pool of water instead of a desert before us. Or like Abraham stopped by the angel, we might be able to see something other than our families to sacrifice. We might truly begin to experience the people before us, and the world before us anew.

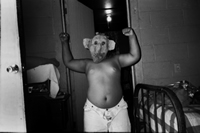

We too want to be seen anew. We all want to be seen. To be heard. I think of my son Nativ. He loves to play hide and seek with me when I come home. The dialogue goes something like this….I walk in the door and Nativ calls out, “Abba, I’m hiding.” I ask my wife, “Hey, where is Nativ?” She will say, “I don’t know he was here a minute ago.” And then Nativ calls out from under the kitchen table or behind the couch, “Abba. I’m here.” More than wanting to hide we want to be found.

We do not want to live in other people’s blind spots. We do not want to be invisible to the world. We do not want to be ignored. We want to feel understood. When his student gave my friend Tony a photo she had taken of some cracks in the sidewalk, he thought it was a mistake. But then the student explained she planned to send them to the school superintendent with a note saying, “Since you are sighted, you may not notice these cracks. They are a big problem since my white cane gets stuck.” Not only do we shape what we see, but we shape what others see as well. We push things in and out of their blind spots as well as our own.

The violinist who was accustomed to playing before huge crowds was asked what it was like to be cast to the margins. “It was a strange feeling, that people were actually ignoring me,” he said, “I started to appreciate any acknowledgement, even a slight glance up. I was oddly grateful when someone threw in a dollar instead of change.” This was from a man who can earn $1,000 a minute during a performance. “There was this thought, What if they don’t like me? What if they resent my presence…”

I suspect that is how it is for most of us. We don’t need thunderous applause, but we do know the comfort when even one person understands us. And we know the vulnerability of being made invisible. Imagine if one of the world’s greatest violinists can start to doubt his abilities how much more so with us.

I once had a conversation with a homeless man in a shelter. He didn’t start out homeless. In an earlier life he had a successful career in government, but alcohol got the best of him. He explained to me that the hardest part about life on the street was constantly being stepped over, forgotten, ignored.

We want to be heard for who we truly are. We want to be accepted – to be seen. We want to be found. And it does not matter if you are a freshman leaving home for the first time or the grandmother of that freshman, we want someone to say at last, I see you. I hear you. I am with you. We diminish the humanity of others by not seeing them, and we diminish our own by letting it happen.

The cure for our blindness. The thing that will remove the cataracts from our souls is if we direct our hearts to the face of the other before us. If we seek their humanity and stop hiding from our own. We can not distill our lives to a play-list – no matter how good it may be. Your Facebook profile will never contain your essence – It will never allow you to comfort a friend. And it is never, ever a way to say I am sorry. It will never show your true face. Your Blackberry, Iphone or laptop can not replace a conversation. And except for possibly the Iphone it will not help you see beauty, or genius.

Turn them off. Put them away. Lift up your eyes and you will see. Listen and you may hear. Direct your hearts. Pay attention. The people who see the deepest know how to look. The people who know how to hear, have learned how to listen. I challenge you all to unplug for a weekend or forever– at least for the next 24 hours. No television or computers, no cell phone, no text messaging, no IM, no email and no Facebook. Just face to face conversations or comfortable silences. And then, maybe then, our vision will be restored.

Im shemohah, tishmah – if you listen you will hear. “If you listen to what is old, you will hear what is new.” The struggle is to let go of our distortions – whether caused by fear or distraction. And seek a higher illumination – see beyond sight. See the face of the other.

And that is what we need to commit and recommit to again. And again. And again. We have to look close enough. We need to not only listen but also strive to hear. We need to really see. Not what we expect to see, but what is really before us. Who is really before us. And then we might discover in our closest relationships something fresh and unexpected. Something completely new or recover something very old or forgotten.

We have to keep looking and searching and exploring and seeking until we arrive where we began and see the place, see their faces for the first time. Our relationships, our lives, our very souls depend upon it. And then if we look a bit closer, and closer still, in the sound and the silence, in the white fire and the black fire, at what has always been before us. We might begin to see, shimmering there, the fine threads binding our lives, and our souls together.

The metaphors from Seeing Beyond Sight find resonance across various religious beliefs. Below you will find examples of how the stories from the book have been used in Jewish and Christian and Buddhist traditions.

If you deliver a faith-based message using stories from the book, contact us and we'll be happy to consider including it for many others to see.